The word Etiquette comes from the French word étiquette, which means prescribed behavior[1]. Etiquette “is a code of behavior that delineates expectations for social behavior according to contemporary to conventional norms, within a society, social class or a group”.[2]

Any concert (specially of classical music) has some specific rules in order to let the musicians and also the audience to be able to concentrate during the performance. This etiquette is well known by the audience and normally avoids creating unwanted distractions.

Some concert halls have their own etiquette protocol, which are just some well-known rules. Here is an example of a music booklet from a concert at the University of San Diego[3]:

· “Arrive at the concert venue at least five to ten minutes ahead of the concert, to purchase your ticket, find your seat, take a program, and be seated. Conversations with companions or those seated nearby is appropriate and welcome, but as soon as the concert begins, discussion should cease.

· Once the concert begins, do not leave the seat except in cases of dire need or emergency. If you must get up, try to do so between selections. If possible, wait until the audience is applauding before leaving.

· During the performance, it is absolutely important not to talk, sing along, hum or yell (whether positively or negatively). If necessary, a discreet whisper to your companion may be acceptable if it occurs infrequently, but the general rule is to keep your attention focused upon the performance in front of you.

· If you are taking notes on the performance in preparation for a concert report, please use paper and pen. Please turn the pages of your notebook quietly and when the music is not being played.

· Please do not write notes to your neighbor. Keep your attention focused upon the performance in front of you.

· Do not bring a laptop into the concert venue. Clacking keys and the glare of the screen will distract others.

· Cell phones, pages, and watch alarms should be turned off or set on vibrate. It is best to put cell phones away in case one has an overwhelming urge to check text messages or play games.

· No food or beverages are allowed inside the concert venues at USD. However, bottled water is allowed.

· It is customary to applaud when the conductor and/or the musicians first come out on the stage. The will bow to acknowledge the audience´s applause and the concert will begin.

· When you read your program, you will probably notice between two and five major compositions of music, with several movements listed as subcategories of each. It is best not to clap between movements of a larger composition. Certainly, though, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate between movements and keep track of where the performers are in the course of the program, particular if you are unfamiliar with classical music. Therefore, if you are unsure of whether or not clapping is appropriate, follow the lead of the experienced audience members around you.”

This is a good example of how this protocol leads the audience to avoid any disturbance during the presentation. It also helps the audience, as well as the musicians, to be concentrated on the main goal of the concert, which is the transmission of music.

In Germany the term etiquette is also known as “Knigge” referring to the Baron Adolph Franz Friedrich Ludwig Knigge, a German writer and Freemason who wrote the book “Über den Umgang mit Menschen” (On Human Relations). This work is in fact more of a sociological and philosophical treatise on the basis of human relations than a how-to guide on etiquette [4].

There are also teaching programs for children promoted by concert halls, like the Gürzenich Orchestra from Cologne, which offers the small audience an etiquette course for the concert, called “der kleine Konzertknigge”[5]; this course will finish with a classical concert. Music schools play a big role in the concert protocol: besides teaching young students this etiquette rules, they also offer etiquette courses for the inexperienced audience (e.g. a music school from a small town in Bavaria called Inning[6]).

2.1 The Silence in the Concert Hall

Normally this protocol is focused on keeping silence in the hall, and therefore allows total concentration. In 1952, US composer John Cage wrote a piece where the score instructs the performer not to play the instrument during the entire duration of the piece. The main idea of the piece was to emphasize the sounds of the environment.

“I think perhaps my own best piece, at least the one I like most, is the silent piece 4’33". It has three movements and in all of the movements there are no sounds. I wanted my work to be free of my own likes and dislikes, because I think music should be free of the feelings and Ideas of the composer. I have felt and hoped to have led other people to feel that the sound of their environment constitute a music which is more interesting than the music which they would hear if they went into a concert hall.”[7]

This piece breaks the perception of a concert. Sounds are not produced by musicians, but instead by the audience. The piece might also be regarded as silence, although Cage proved that we cannot actually hear it:

“There´s no such thing as silence. What they thought was silence (in 4’33"), because they didn´t know how to listen, was full of accidental sounds, you could hear the wind stirring outside during the first movement (in the premiere). During the second, raindrops began pattering the roof, and during the third the people themselves made all kinds of interesting sound as the talked or walked out” [8]

At Harvard University, Cage was in an anechoic chamber (“a non echoing chamber which is designed to stop reflections of either sound or electromagnetic waves”[9]) and there he listened to the silence: “But I went into an anechoic chamber in Cambridge, at Harvard University, and in this room I heard two sounds. I thought there was something wrong with the room, and I told the engineer that there were two sounds. He said describe them, and I did. “Well, ” he said, “the high one was your nervous system in operation and the low one was your blood circulating.”[10]

Normally, “an Anechoic Chamber has noise levels between 10 to 20 dBA”[11]. The threshold of hearing “the faintest sound that a human ear can detect”[12] has an intensity level of 0dB. According to this experience, it would make no sense to call silence the absence of any sound in a concert room or elsewhere.

A good concert hall has noise levels around 25 – 35 dBA[13], but normally we hear unwanted sounds like the air-conditioning systems and, of course, the noises of the audience.

This was the main conception of my concert, because it is not possible to isolate a concert from unwanted sounds, even when the audience is really quiet (which is almost impossible), there is always going to be some kind of distractions. Therefore, I decided to play with these sounds (which normally we want to avoid) and make them part of the concert. In fewer words, everything that we listen in a concert is part of the concert.

2.1.1 Coughing in a Concert

It is very common to hear people coughing or sneezing in a concert. For decades, the US-American baritone Thomas Hampson experienced a lot of interruptions, making possible for him to be able to develop a “Cough’s Typology”[14].

“1. Das Entlastungs-Hüsteln (staccato forte)

Ein relativ kurzes Hrr-Hmm!, die häufigste Ausdrucksform im Zuschauerraum. »Husten ist menschlich«, sagt Hampson. »Nur, seltsamerweise wird fast nie gehustet, wenn die Musik sehr laut ist, obwohl es da am wenigsten stören würde. Wird die Musik aber leiser, geht es los: Hrr-Hmm!« So werde bei leisen Stücken von Claude Debussy sehr viel, bei lauten Sinfonien von Peter Tschaikowsky sehr wenig gehustet. Hampson hat eine Theorie, was diese Räusperer anbelangt, sie beruht auf der Beobachtung, dass sich im Kino niemand räuspert. »Mein Eindruck ist, Menschen haben als soziale Wesen das natürliche Bedürfnis, mitzusingen, so wie Vögel. Deshalb sind ihre Stimmlippen während eines Konzertes in ständiger Anspannung.« Folgt auf einen lauten Satz eine leise Passage, entspannen sich die Stimmlippen, und es wird ausgerechnet dann gehustet, wenn es am meisten stört.

2. Der explosive Stoßhusten (sforzando forte)

Ein explosionsartiger, vollhalsiger Huster ohne Taschentuchdämpfung, wahlweise am rührendsten oder leisesten Punkt einer Oper: Ächh-Hmm! Ächh-Hmm! Besonders ältere Menschen neigten dazu. Wie in einem Strafprozess möchte Hampson hier zwischen Vorsatz und Fahrlässigkeit unterscheiden. Sollte sich jemand absichtlich zu so einer Störung entschlossen haben, sei das ein »Attentat übelster Art«. Verständnis hingegen hat Hampson für Menschen, denen das Missgeschick aufgrund einer Atemwegserkrankung passiert, das sei keine Schande. Als Zuschauer hat er allerdings, wenn er selbst husten musste, schon Konzertsäle verlassen – aus Rücksicht auf die Sitznachbarn. »Man sollte nie unterschätzen, wie laut ein Husten ist.« Würden die Konzerthäuser eine große Hustenreform anstoßen, fielen Hampson Sofortmaßnahmen ein: Bonbons und Wasser für jeden Zuschauer.

3. Der Abonnenten-Husten (tenuto mezzoforte)

Ein ausführliches, den Hals vollständig von allen Verstopfungen befreiendes Husten zwischen zwei Sätzen: Hhhh-Ääächh! Hhhh-Ääächh! Charakteristisch ist der lang gezogene Rachenlaut: chh! Diese Form des Hustens ist vor allem vom erfahrenen Abonnement-Publikum zu hören. Legitim, meint Hampson, aber nicht völlig unproblematisch: »Das Husten zwischen den Sätzen ist höflich gemeint. Die Menschen müssen aber verstehen: Solche Pausen sind keine Freiräume für menschliche körperliche Bedürfnisse. Das sind keine Raststätten auf der Autobahn. Musik ist eine Sprache, und die Stille ist einer ihrer wertvollsten Bestandteile.« Am besten wäre es, die Zuschauer würden beim Anfangsklatschen, während der Dirigent den Raum betritt, »sich ordentlich räuspern«, um dann den Rest des Abends gar nicht mehr zu husten.

4. Das ansteckende Räuspern (martellato subito)

Ein beiläufiges, schnelles Husten als Reaktion auf das Husten eines anderen Zuhörers: Hrrchh? Hrrchh! Wie die Geige das Thema der Sinfonie von der Klarinette übernimmt,nimmt hier der Huster den Bronchiallaut seines Sitznachbarn auf und variiert ihn leicht. Besonders bei Klavierabenden und Streichkonzerten kann dies ein »unfassbarer Störfaktor« sein, so Hampson. »Einer erlaubt sich, ordentlich Hrrchh! zu husten, dann denkt der Nächste, na, Donnerwetter, das kann ich auch: Hrrrchh! Könnte jemand, der krank ist, nicht das Opfer bringen, zu Hause zu bleiben?« Hampson sagt das mit einem Augenzwinkern, es gibt Schlimmeres als einen Huster zwischendurch. Trotzdem glaubt er, dass sich die Lautstärke von Hustern stark verringern lasse, indem man die Hand oder ein Taschentuch vorhält. Das Vorbild sei Japan, dort werde nie gehustet.

5. Der große Würgeanfall (fermata, crescendo, staccato, echo)

Ein unterdrückter Reizhusten, gegen den der Zuschauer aus Höflichkeit mit tränenden Augen ankämpft und verliert: Hrrr. Hrrrr. Gnnnn – Ähem! Ähem! Ähem! Besonderes Merkmal sind die Zwerchfellkrämpfe und das knallrote Gesicht der Leidenden, »Kürbisköpfe« nennt Hampson dieses Phänomen. Obwohl er beim Singen eigentlich über die Köpfe hinwegschaut, bleibt sein Auge manchmal an den »Kürbissen« hängen. Spätestens wenn Sitznachbarn versuchen, den von Zwerchfellspasmen Geschüttelten mit Klopfern auf den Rücken zu helfen, bekommt auch der Bariton Mitleid. Manchmal erinnern ihn solche Hustenkonzerte an Loriot, der in einem seiner Sketche ein Sinfonieorchester dirigiert und die Huster des Publikums gleich mit. Das Ganze verschmilzt zu einer wunderbaren Kakophonie aus Röcheln, Niesen und klassischer Musik.”

2.1.2 Recording in a concert

Nowadays most of the concerts are recorded. Mobile recordings or onsite recordings not only save money, but also time. Recording a symphonic orchestra in a concert hall provides a better acoustic as in a recording studio. Thanks to the advances in portable audio equipment, this setup is really practical and can prove itself as good as the studio equipment. Audio industries take advantage of some concerts and live presentations, transmitting them on radio or Internet and finally editing them in order to have a commercial audio product (CD – DVD).

For example, Berlin Philharmonic’s “Digital Concert Hall”[15], which offers a high quality live transmission of all its concerts online, including trailers and artist interviews. Users in any place in the world are able to see the concert on the computer and also on TV. Besides, it has an online archive with more than 119 concerts.

Live-recorded concerts are an extra reason to give more importance to the concert protocol, in order to have a high quality recording. It is not desired to have a cell phone ringing or someone coughing in a live recording.

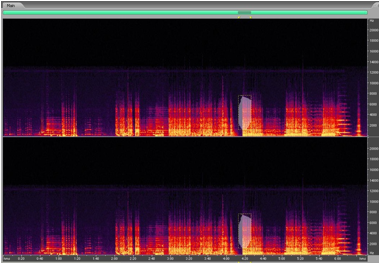

Thanks to Non-Linear Audio Editing systems (NLAE), which can perform random access non destructive editing[16] (allows to edit any part of the whole without modifying or destroying the source material) in the source material (in this case the recorded concert) and specially spectral tools, it is possible to remove unwanted sounds from concerts like background noises, coughs etc., and therefore clean the recording.

The next picture is an example of a non-linear audio editing software using the spectral frequency display that, with the help of the lasso tool, allows to select specific frequencies in order to be removed or modified.

Adobe Audition Software - Spectral Frequency Display (time vs. frequency)

However, the best way to remove an unwanted sound is to avoid it. Just the fact of having the musicians surrounded by lots of microphones will intimidate the audience and invite them to remain silent in the hall. In some cases it is also possible to have an interlocutor who invites the audience to collaborate by keeping calm. It would be unpleasant to applaud in a “wrong moment” and destroy the recording. Applause distractions or interruptions will be explained later, because they are playing a structural role.

2.2 The Concert Structure

Each concert has a macro structure and its main goal is to help the listener to easily perceive the music and enjoy the whole event. The sequence of the pieces is also organized in order to create dramaturgy. It can describe a chronological order, as well as any other kind of organization. Normally in popular music concerts a set list is used in order to keep the audience active, practically the opening song and the closing song being the most important ones in the show. These songs are mainly the hits of the band and the last one should invite to have an encore or an extra song. In popular music, as well as in classical music, the final applause will invite to have an extra piece and most of the times the musicians have already planned it.

The classical concerts of today usually have a break, because they are quite extensive (around two hours), and it is necessary to have some relaxation time at some point, otherwise the focus of the audience and of the musicians will be affected. This pause is also used to arrange logistic issues during a concert, for example to organize the instruments on stage. Complex concerts, with electronic or multimedia pieces for example, also need a pause at some point, in order to avoid possible problems and allow further preparations of the technical setup.

In live-electronics concerts the order of the pieces also has to do with the preparation of the next piece. Composers, and sometimes technicians, prepare the structure of the concert, in order to have smooth transitions without big pauses between the pieces. Otherwise the concentration of the public will be affected and, in the worst case, they will start complaining and creating a possible stress situation for the composer, the technicians or the musicians.

To avoid this situation in my concert, I decided to use tape-pieces as a joker, in order to prepare a technically complex piece, especially while preparing the patches that could have taken some time to load, but also to have a grace time in case of problems.

I decided to make a short concert without any pause, where the applauses were not leading the development of the concert. The pieces of the Multimediaabend – Hemmungslos were not separated, they were crossfaded with the purpose of avoiding applause, to create confusion in the audience and, therefore, to create a different experience where the audience does not have any idea of the structure of the concert.

2.2.1 Applause as traffic light in a concert

The applause is a powerful element in a concert and the only chance of the audience to express itself. It is a way to communicate the successes of the concert, but also to lead and separate the pieces of the concert.

As already shown in the University of San Diego’s booklet, the applause is really important in the concert protocol. Nowadays in a classical concert, one is only allowed to applaud when the piece is completely finished, it is forbidden to applaud between movements and this is the main worry of many amateurs in a classical concert. The best advice for this kind of audience is to wait for the applause of the others who know the piece and when it is finished.

In Fall 2009, Barack Obama hosted an evening of classical music at the White House, where he spoke about the rule of the applause. He gave as example the US American president John F. Kennedy that had the same problem: “He and Jackie held several classical-music events here (Wigmore Hall) and more than once he started applauding when he wasn´t supposed to. So the social secretary worked out a system where she´d signal him trough a crack in the door to the cross-hall. Now, fortunately, I have Michelle to tell me when to applaud. The rest of you are on your own.”[17]

"The word 'applause' comes from the instruction 'plaudite', which appears at the end of roman comedies, instructing the audience to clap".[18]

Alex Ross, a US American music critic, held in 2010 a lecture in London explaining the importance of the applause in the classical concert. He also used as example a program booklet that said, “Thou shalt not applaud between movements of symphonies or other multisectional works listed on the program.” For him this applause protocol means in essence, “Curb your enthusiasm. Don´t get too excited.”[19]

Ross affirms that “the No-Applause Rule was originated in Germany, and changed quickly because at the turn of the century mid-symphonic applause was still in routine”.[20] He mentioned examples where the rule was still in use, like the performance of the Fourth Symphony of Brahms in Vienna in 1987, the First Symphony of Sir Edward Elgar, where the composer was called out several times after the first movement, or the Pathétique Symphony of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, where each movement was heatedly applauded.

The music critic also mentioned the “reform of the concert hall” that was described by Heinrich Schwab and Walter Salmen, which was the topic of discussion in German music journals in the period after 1900. This reform suggested, “that concerts should be presented in subdued light and that orchestras be hidden behind a screen; and it was proposed that no one should applaud until each work was done”.[21]

“The hidden orchestra did not catch on, but the No-Applause Rule did”. Alex Ross mentioned the young conductor Hermann Abendroth, who “during concerts in Lübeck in 1945 instructed his audience not to clap between movements of a symphony” and Karl Klingler, “the leader of the Klingler quartet, who took credit for instituting the No-Applause Rule at his Berlin Concerts during the 1909-1919 season”.[22]

Today, this rule is completely established and we normally ignore they way it was in the past. The best example is the letter Mozart wrote to his father in 1778, concerning the premiere of the “Paris” symphony in Paris.

“Right in the middle of the First Allegro came a Passage that I knew would please, and the entire audience was sent into raptures—there was a big 'applaudißement';—and as I knew, when I wrote the passage, what good effect it would make, I brought it once more at the end of the movement—and sure enough there they were: the shouts of Da capo. The Andante was well received as well, but the final Allegro pleased especially—because I had heard that here the final Allegros begin like first Allegros, namely with all instruments playing and mostly unisono; therefore, I began the movement with just 2 violins playing softly for 8 bars—then suddenly comes a forte—but the audience had, because of the quiet beginning, shushed each other, as I expected they would, and then came the forte—well, hearing it and clapping was one and the same. I was so delighted, I went right after the Sinfonie to the Palais Royal—bought myself an ice cream, prayed a rosary as I had pledged—and went home”.[23]

It´s very interesting to see how these rules and its background affects the development and essence of a concert. I do not pretend to affirm what is the correct way to apply this etiquette in a concert, I just pay attention to the reaction of the people under these circumstances and enjoy to see the uncertainty of the audience.

It is quite common in a classical concert, once the musician has finished the piece, to notice a short pause of time when the audience does not know if to applaud. They already know that the piece is finished, but they are still waiting for the wink of the artist. Usually, either the artist is waiting for the applause or he needs some silence to internalize the piece.

On the other hand, in jazz concerts the musicians improvise constantly during the pieces and these improvisations are normally followed by applause. In most jazz standards musicians improvise on an instrument, so it is normal to have more than three rounds of applause in one single piece…. not to mention pop/rock and folk concerts, where the public applauses freely.

2.2.2. Hall Concert and Street Concert

The rules between these two different scenarios are not the same: the rules posted before normally apply in the concert hall, but not in street presentations.

What I found important in the “public art”[24] is the fact that art comes to you and not the other way around, thus there is a greater chance of surprising the visitor and making the work even more interesting. Personally, I enjoy “art intervention”[25] – this kind of art was also implemented in my concert through an audio installation in the bathroom of the concert hall.

I remember an art intervention in the bathroom of the Centre d’art Contemporain in Genève. After hours of walking between many contemporary works, most of them uninteresting to me, I went to the bathroom and I was surprised to see a lot of ants in the corner of the wall, close to the urinal. One understands very quickly that all these animals are just a painting (they are not moving), but the effect was so realistic that I had to get closer to be sure. I left the bathroom and did not want to find any information about neither the work, nor the author, I just wanted to keep that experience in my mind. It was probably one of the best works that I saw that day and it actually inspired me later to work in public spaces, especially in the bathroom.

The Multimediaabend – Hemmungslos mixes these two different scenarios and also tries to offer the visitor a chance to see art where he is not expecting to see it.

2.2.3. The Interaction Ritual

Erving Goffman, a Canadian sociologist known for his study of symbolic interaction, deals with social circumstances as a mise-en-scène. He believed that “all participants in social interactions are engaged in certain practices to avoid being embarrassed or embarrassing others”[26]. This is why people try to refrain from producing unwanted interruptions like coughing, sneezing or even applauding during concerts: they want to avoid embarrassment. According to Eduardo de la Fuente, 4’33" also inspired Goffman. This piece has an important aesthetic implication: “sound is predicated on expectations that are framed by cultural meaning and social context”[27]. So that is why the best place to show the meaning of 4’33" is in a concert hall, although there are also examples of this piece being played on the street.

In the classical concert, the social context is the concert hall. A classical concert hall is an elitist place where people try to enjoy the sounds of the music, while trying to ignore all other sounds. Each character has its own roll: the director of the orchestra, the interlocutor, the musicians and, finally, the audience, which in most cases is limited to applaud when they need to.

Any irregularity of these roles will induce to embarrassment, doubt and insecurity. We are acting and interacting all the time. I do not pretend to explain why and how these roles are present and how they influence our behavior. My concert is a way of showing us – musicians and audience – that we do not have everything under control and that we should also leave spaces to express ourselves, especially in a concert situation.

[1] Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=etiquette

[2] Memidex Dictionary. http://www.memidex.com/etiquette

[3] “Attending a classical music concert”. Concert Booklet found on Internet - University of San Diego. http://www.sandiego.edu/cas/documents/music/guidelines.pdf

[4] Wikipedia Encyclopedia. ttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolph_Freiherr_Knigge

[5] Gürzenich Orchestra. http://www.guerzenich-orchester.de/jugend/musik_und_tanz/

[6] Der Kleine Konzert-Knigge. http://www.musikschule-inning.de/wie/knigge.html

[7] Richard Kostelanetz. Conversing with Cage. p70

[8] Richard Kostelanetz. Conversing with Cage. p70

[9] Wikipedia Encyclopedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anechoic_chamber

[10] Richard Kostelanetz Conversing with Cage 2003. p423

[11] What is An Acoustic Anechoic Chamber? http://www.acousticpc.com/re_anechoic_chamber.html

[12] The Physics Classroom. http://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/sound/u11l2b.cfm

[13] The Engineering Toolbox. http://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/nc-noise-criterion-d_725.html

[14] Stören in Konzert, Zeit Online. http://www.zeit.de/2011/14/Konzert-Typologie-des-Hustens

[15] Berliner Philarmoniker - Digital Concert Hall http://www.digitalconcerthall.com/de/info

[16] Wikipedia Encyclopedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-linear_editing_system

[17] Hold Your Applause: Inventing and Reinventing the Classical Concert. Alex Ross Lecture at The Royal Philarmonic Society. http://alexrossmusic.typepad.com/files/rps_lecture_2010_alex-ross.pdf

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Robert Gutman. Mozart: a Cultural Biography. p430-431

[24] “In simple terms, public art is any work of art or design that is created by an artist specifically to be sited in a public space”. What is Public Art? – Newport News Public Art Foundation. http://nnpaf.org/what_is_art.html

[25] “Intervention can also refer to art which enters a situation outside the art world in an attempt to change the existing conditions there” – Art Intervention. Wikipedia Encyclopedia.

[26] Eduardo de la fuente. Twentieth century music and the question of modernity. P131.

[27] George Ritzer. Sociological Theory. P372.